Thursday, February 25, 2010

MOVING TO A NEW, BETTER, SITE: www.hdscienceblog.com

Sunday, February 21, 2010

CHDI Therapeutics Conference in Palm Springs

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Latin American HD Network: Thoughts after the Initial Meeting

This chapter, like many others, begun from the desire to help others, to not forget those less fortunate to have access to the same resources I and some of my Americana and European colleagues have. I was aware of the fact that the gene for Huntington's disease (Huntingtin) was identified through a heroic effort of a multinational team of scientists, who used DNA obtained from the blood samples of a large set of families from a region in Venezuela bordering Lake Maracaibo in the north west of the country. In this area, the prevalence of Huntington's disease was high; there were large families with 3 or 4 generations of affected individuals, which allowed for the type of genetic analysis necessary to identify genetic contributions to the disease. Through a process called 'positional cloning', patterns of inheritance of DNA regions, or 'markers', can be traced to isolate regions where the disease gene resides. These regions became progressively better 'mapped' and this lead to the final identification in 1993 of the gene harboring the mutation responsible for HD. The pictures below are from some of the Venezuelan patients, next to a wonderful person named Aleska de Zambrano, who is the voice of the Venezuelan HD patient and families association.

The importance of Latin America, and Venezuela in particular, has already been large in the field of HD. There are other regions in Colombia and Brazil, and probably others I don't know of as of yet, where HD is highly prevalent. Yet the representation of our efforts in Latin America, from a scientific and clinical perspective, is small. It is almost as if Latin American countries were largely kept 'outside' of many scientific and medical international enterprises. I felt we could do something to change this. I also thought that we needed our colleagues, doctors and scientists, as well as patients and their families, to be more actively involved with the efforts of CHDI. I was aware that recruiting patients for clinical and observational trials was proving challenging, and if we are to develop medicines, we will necessarily need additional patient participation, and also probably additional clinical sites to conduct these studies.

Through my friend Gerardo Jimenez, the then director of the Institute of Genomic Medicine in Mexico, I organized a visit to the National Institute of Neurology, where we met the team coordinated by Dra. Elena Alonso, the director of the medical genetics department. Even though this meeting was rather unsuccessful in initiating efforts to bring our efforts together with theirs, it represented an initial step in consolidating our interest in working with our Latin American colleagues. I invited Dr. Bernhard Landwehrmeyer, from Germany, who is the acting chairman of European HD Network (www.euro-hd.com), and a very accomplished scientist and neurologist. EHDN has established an impressive network through most of Europe of clinicians, patients, scientists and advocacy groups (this network is funded exclusively by CHDI). Bernhard was part of the initial team of scientists headed for Venezuela. His passion and dedication to help cure this disease are unparalleled. He immediately responded to my invitation to come to Mexico and shared his (unknown to me at the time) long standing desire to make a Latin American Network a reality.

Through the support of Robi Blumenstein (the President of CHDI), myself, Bernhard and Dr. Michael Orth from EHDN, organized the first meeting of clinicians and patient groups in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) this past Feb. 05 and 06. The meeting brought together neurologists and patient representatives from Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Chile, Venezuela and Spain. The meeting was chaired by Dr Francisco Cardoso of Belo Horizonte (Brazil), who managed to get together several prominent neurologists, to discuss both the incidence and management of HD care in their countries, as well as to discuss common interests in establishing the network. Representatives from Colombia and Peru were unable to come, but will undoubtedly participate in future events. We discussed our vision for why having a Latin American network is important for CHDI and EHDN; why we think that by working together we can maximize the changes of being successful and shortening the time to an effective treatment. A few hours before the meeting begun in Rio, we received notice of the positive preliminary outcome of the ACR-16 trial (carried out by the company Neurosearch in collaboration with EHDN). It was an auspicious beginning. The meeting proved a clear success in terms of excitement among our Latin American colleagues, both the doctors and the lay people. The meeting lead to a selection of an initial committee to consider formalizing such network, and beginning to craft a set of initial objectives, a mission and a constitution for how they want to operate. We agreed to meet next in Buenos Aires in June for the International Meeting of the Association for Movement Disorders.

I don't know what my longer term role will be, as this is outside of my 'day job'… I can only thank the people who have participated and are trying to make this network a reality. I feel that HD is a global disease and therefore our efforts should be global. That together we have a stronger chance at defeating this disease. During the meeting, I met many patients and relatives, who came from all over Brazil, some from far away. They came to talk to us, to ask questions about whether there was any hope of finding any treatments soon… I felt powerless, frustrated, almost emasculated… I could not give them much good news yet… I realized my struggles with work and life are petty compared to the anxiety of knowing that a certain and terrible death awaits them and their relatives, their spouses and children. No statements such as 'please be patient', 'it takes years to do a clinical study', 'we don't understand the disease enough' make justice to the fear of imminent death for those one loves. They sound like a set of excuses for not being able to help… and yet I know we do the best we know, the best we can, to find answers. I went to Rio because I wanted to extend a message of Hope to those in Latin America – this is not an American or European enterprise, it's a global fight to find a cure, which should be made available to all, rich or poor, in NY or Maracaibo. But I also went there because we need more people to work with us. I need every affected person to participate: by donating blood, by speaking out, by enrolling in observational studies, in clinical studies. We simply cannot do it without the patients and the people at risk.

When I was asked many questions about potential therapies, like stem cell transplantation studies, I failed to understand their desperation. I want to communicate to them that right now there are no therapies available, and that therefore they should not expose themselves to treatments unknown to be effective, and which can cause them a lot of harm. My only advice is that they need to educate themselves, through the patients' international or national associations, and through their doctors. The patients should not remain paralyzed, waiting for a pill. There are ways to get involved, and we need to raise that awareness. Go to the following websites: HSG, HDF, EHDN and CHDI. Reach out and ask questions to those who only have the best interest of the patients in mind. I almost cried feeling the sincere gratitude the families and patients expressed to us. Because we had come to them, to be able to converse and answer some of the many questions they have. I left with a strong feeling of urgency, but also of fulfillment, of gratitude for being able to live this moment, and of being able to help in whatever way possible. After all, this is why I became a scientist… so thank you to all who believe in our mission and who understand that there are good scientists working for your health and your life. Obrigado!

Saturday, January 30, 2010

The beginning of my diary as a scientist

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

TRACK HD publication

The goal for this comprehensive evaluation is 2-fold: first, the researchers need to identify the most sensitive tests which identify the most people (at risk for HD) which are showing symptoms of the disease (even before the traditional diagnosis of the disease, which is typically made by neurologists based on the motor symptoms defined as chorea, or abnorma uncontrolledl movements). The identification of such tests is an essential process to identify novel therapies which might be effective in delaying or improving the symptoms of HD. The current rating scales (typically, the UHDRS, or unified HD rating scale) does not incorporate sufficient tests in the cognitive or psychiatric domains, and therefore it is not a useful scale to assess for efficacy in these domains. This represents an area of considerable importance in developing new therapies, one that is usually not accounted for when conducting clinical trials.

The second goal is to understand the evolution of the symptoms - can we predict when someone at risk to develop HD will develop obert symptoms? Ideally, we would like to start treting patients before the disease is fully developed. Therefore, we need to monitor subjects at risk and understand when is best to start treating them. In order to do this, the authors of the manuscript are monitoring unaffected subjects, people with diagnosed HD, and people carrying the mutation, but who are not yet 'diagnosed' with HD because their symptoms are below the detection level of the UHDRS. What the authors are trying to do is to see how these people perform on all these tasks, to understand how the disease develop (as some of the 'carriers' will develop HD during the course of the study) and how variable the performance on these tasks is over time.

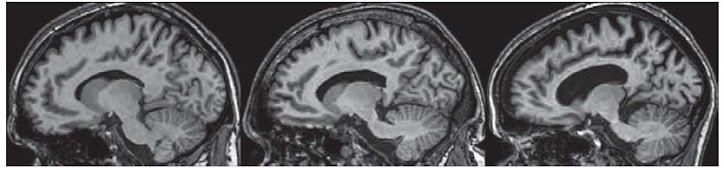

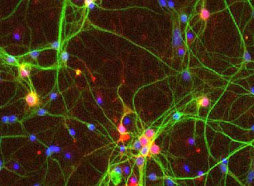

Several findings are notable in the study. One of the most significant findings is that, even in people who are expected to develop HD ten years from now, there are significant differences from unaffected people. Among these, one of the most significant changes is anatomical. The brain regions that degenerate (where the neuons die) in HD are already very affected in un-diagnosed HD carriers. Essentially, one can describe this as being a 'hole' in their brains. Scary? Yes. But.... think about the fact that largely, these people can lead normal lives. They dont have symptoms that physicians would think need medication. This is good news: the brain is capable to operate normally even if many neurons are already dead. I think this offers HOPE since if we are able to slow down the progression, patients might be able to lead normal lives.

Another finding is that there are many tests which are sensitive enough to select 'people at risk' with unaffected people (carryign a normal gene). Some of these tests involve motor coordination (such as finger tapping or a test monitoring what is called saccades (the movement of the eyes directed at following an object that is itself moving within the visual field). In both of these tests, people with HD or people carrying the disease, perform less well than normal subjects. Because the brain areas which are responsible for being able to perform these tasks (for instance, if you are asked to maintain a constant rhythm when tapping your fingers) are the same areas in which the neurons of the brain die over time, these are very 'sensitive' tests that there is a problem in that part of the brain.

Other tests such as apathy and irritability also show significant differences between people at risk and unaffected subjects. Overall, this study is very good news for the HD community: it shows that there are several sensitive tasks that can identify who is at risk, and who might be starting the symptomatic process which will culminate in a clinical diagnosis of HD.

One additional comment: all of the centers which participated in this study, which recruited close to 100 subjects in each group, are outside the USA. why is this? how come it is so difficult to get Americans to enroll in these studies? Maybe it has to do with the fact that the US does not have a national health plan? maybe that insurance companies in the US are still discrimating against people at risk for a chronic lethal disease? All those affected should act in whatever way they can to change these terrible social aspects - all people deserve to have health insurance, and to be treated in the best way possible!

Finally, soon the results from the second year will come to light. It is important to know whether some of these tests which were able to distinguish unaffected subjects from people at risk are good tests to assess whether people are doing 'worse"- this would be a good outcome, since it will mean that these test can assess whether a new therapy makes things better! Lets keep our fingers crossed!!

have a great day and see you soon!

.jpg)