Saturday, January 30, 2010

The beginning of my diary as a scientist

I have decided to change the blog content- i want to use it more like a 'diary' of my scientific life. hopefully i can help make people understand how scientists do their job, and our daily struggles at work and with science. I have also made my identity known. I am the head of biology at a non for profit foundation (www.chdifoundation.org) trying to develop medicines for HD. I oversee work carried out around the world by many teams of dedicated people, whom we contract work to develop medicines and find out how HD develops and progresses. We fund work in basic and applied research, and I work with a very talented set of chemists, biologists, pharmacologists and clinicians. I also work with project managers, business and legal people who help make our foundation a reality. We all work together to develop treatments for HD. I want to show you how I think about this problem, and the issues that I, like most scientists, have to solve to translate ideas to medicines. It is a long process, sometimes tiring and frustrating, because we don't know enough. But we try, as hard as we can, to develop rational approaches based on our current understanding of the brain and of the human body. We could not do this alone, science is built out of a history of studies and on the shoulders of many generations of people who have dedicated their lives to understanding how the brain works and what happens when things fail to work properly. Science is never a lonely enterprise, even if our daily work sometimes is. We are preceded by a history of knowledge. We generate a legacy to our successors, who will inevitably take our learnings and apply them to advance our understanding of any given process. In spite of how small our contributions might be, they will always help future generations. A small finding might be a clue in the future about something truly meaningful.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

TRACK HD publication

Recently the CHDI Foundation, in collaboration with 4 clinical groups in Europe and Canada (led by Dr. Sarah Tabrizi of London) reported their findings of the first year of a study called 'Track HD. The study is a longitudinal evaluation of disease progression over 3 years. In a longitudinal study, the same subjects are repeatedly monitored (in this case, once every 3 years) to assess how their symptoms and the degree of anatomical brain changes, are varying over the length of the study. This manuscript describes the initial findings from the first year evaluation. The study aimed to monitor general domains of interest to the management of the disease. In HD, there are several 'domains' which are affected: these are related to clinically distinct symptoms, such as anxiety and depression (psychiatric changes), cognitive abilities, and motor components (such as chorea, visual tasks, finger tapping, etc.) In addition, and importantly, the study incorporated imaging studies, where the structures of various anatomical regions of the brain are studied.

The goal for this comprehensive evaluation is 2-fold: first, the researchers need to identify the most sensitive tests which identify the most people (at risk for HD) which are showing symptoms of the disease (even before the traditional diagnosis of the disease, which is typically made by neurologists based on the motor symptoms defined as chorea, or abnorma uncontrolledl movements). The identification of such tests is an essential process to identify novel therapies which might be effective in delaying or improving the symptoms of HD. The current rating scales (typically, the UHDRS, or unified HD rating scale) does not incorporate sufficient tests in the cognitive or psychiatric domains, and therefore it is not a useful scale to assess for efficacy in these domains. This represents an area of considerable importance in developing new therapies, one that is usually not accounted for when conducting clinical trials.

The second goal is to understand the evolution of the symptoms - can we predict when someone at risk to develop HD will develop obert symptoms? Ideally, we would like to start treting patients before the disease is fully developed. Therefore, we need to monitor subjects at risk and understand when is best to start treating them. In order to do this, the authors of the manuscript are monitoring unaffected subjects, people with diagnosed HD, and people carrying the mutation, but who are not yet 'diagnosed' with HD because their symptoms are below the detection level of the UHDRS. What the authors are trying to do is to see how these people perform on all these tasks, to understand how the disease develop (as some of the 'carriers' will develop HD during the course of the study) and how variable the performance on these tasks is over time.

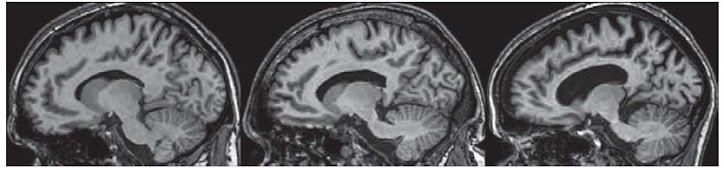

Several findings are notable in the study. One of the most significant findings is that, even in people who are expected to develop HD ten years from now, there are significant differences from unaffected people. Among these, one of the most significant changes is anatomical. The brain regions that degenerate (where the neuons die) in HD are already very affected in un-diagnosed HD carriers. Essentially, one can describe this as being a 'hole' in their brains. Scary? Yes. But.... think about the fact that largely, these people can lead normal lives. They dont have symptoms that physicians would think need medication. This is good news: the brain is capable to operate normally even if many neurons are already dead. I think this offers HOPE since if we are able to slow down the progression, patients might be able to lead normal lives.

Another finding is that there are many tests which are sensitive enough to select 'people at risk' with unaffected people (carryign a normal gene). Some of these tests involve motor coordination (such as finger tapping or a test monitoring what is called saccades (the movement of the eyes directed at following an object that is itself moving within the visual field). In both of these tests, people with HD or people carrying the disease, perform less well than normal subjects. Because the brain areas which are responsible for being able to perform these tasks (for instance, if you are asked to maintain a constant rhythm when tapping your fingers) are the same areas in which the neurons of the brain die over time, these are very 'sensitive' tests that there is a problem in that part of the brain.

Other tests such as apathy and irritability also show significant differences between people at risk and unaffected subjects. Overall, this study is very good news for the HD community: it shows that there are several sensitive tasks that can identify who is at risk, and who might be starting the symptomatic process which will culminate in a clinical diagnosis of HD.

One additional comment: all of the centers which participated in this study, which recruited close to 100 subjects in each group, are outside the USA. why is this? how come it is so difficult to get Americans to enroll in these studies? Maybe it has to do with the fact that the US does not have a national health plan? maybe that insurance companies in the US are still discrimating against people at risk for a chronic lethal disease? All those affected should act in whatever way they can to change these terrible social aspects - all people deserve to have health insurance, and to be treated in the best way possible!

Finally, soon the results from the second year will come to light. It is important to know whether some of these tests which were able to distinguish unaffected subjects from people at risk are good tests to assess whether people are doing 'worse"- this would be a good outcome, since it will mean that these test can assess whether a new therapy makes things better! Lets keep our fingers crossed!!

have a great day and see you soon!

The goal for this comprehensive evaluation is 2-fold: first, the researchers need to identify the most sensitive tests which identify the most people (at risk for HD) which are showing symptoms of the disease (even before the traditional diagnosis of the disease, which is typically made by neurologists based on the motor symptoms defined as chorea, or abnorma uncontrolledl movements). The identification of such tests is an essential process to identify novel therapies which might be effective in delaying or improving the symptoms of HD. The current rating scales (typically, the UHDRS, or unified HD rating scale) does not incorporate sufficient tests in the cognitive or psychiatric domains, and therefore it is not a useful scale to assess for efficacy in these domains. This represents an area of considerable importance in developing new therapies, one that is usually not accounted for when conducting clinical trials.

The second goal is to understand the evolution of the symptoms - can we predict when someone at risk to develop HD will develop obert symptoms? Ideally, we would like to start treting patients before the disease is fully developed. Therefore, we need to monitor subjects at risk and understand when is best to start treating them. In order to do this, the authors of the manuscript are monitoring unaffected subjects, people with diagnosed HD, and people carrying the mutation, but who are not yet 'diagnosed' with HD because their symptoms are below the detection level of the UHDRS. What the authors are trying to do is to see how these people perform on all these tasks, to understand how the disease develop (as some of the 'carriers' will develop HD during the course of the study) and how variable the performance on these tasks is over time.

Several findings are notable in the study. One of the most significant findings is that, even in people who are expected to develop HD ten years from now, there are significant differences from unaffected people. Among these, one of the most significant changes is anatomical. The brain regions that degenerate (where the neuons die) in HD are already very affected in un-diagnosed HD carriers. Essentially, one can describe this as being a 'hole' in their brains. Scary? Yes. But.... think about the fact that largely, these people can lead normal lives. They dont have symptoms that physicians would think need medication. This is good news: the brain is capable to operate normally even if many neurons are already dead. I think this offers HOPE since if we are able to slow down the progression, patients might be able to lead normal lives.

Another finding is that there are many tests which are sensitive enough to select 'people at risk' with unaffected people (carryign a normal gene). Some of these tests involve motor coordination (such as finger tapping or a test monitoring what is called saccades (the movement of the eyes directed at following an object that is itself moving within the visual field). In both of these tests, people with HD or people carrying the disease, perform less well than normal subjects. Because the brain areas which are responsible for being able to perform these tasks (for instance, if you are asked to maintain a constant rhythm when tapping your fingers) are the same areas in which the neurons of the brain die over time, these are very 'sensitive' tests that there is a problem in that part of the brain.

Other tests such as apathy and irritability also show significant differences between people at risk and unaffected subjects. Overall, this study is very good news for the HD community: it shows that there are several sensitive tasks that can identify who is at risk, and who might be starting the symptomatic process which will culminate in a clinical diagnosis of HD.

One additional comment: all of the centers which participated in this study, which recruited close to 100 subjects in each group, are outside the USA. why is this? how come it is so difficult to get Americans to enroll in these studies? Maybe it has to do with the fact that the US does not have a national health plan? maybe that insurance companies in the US are still discrimating against people at risk for a chronic lethal disease? All those affected should act in whatever way they can to change these terrible social aspects - all people deserve to have health insurance, and to be treated in the best way possible!

Finally, soon the results from the second year will come to light. It is important to know whether some of these tests which were able to distinguish unaffected subjects from people at risk are good tests to assess whether people are doing 'worse"- this would be a good outcome, since it will mean that these test can assess whether a new therapy makes things better! Lets keep our fingers crossed!!

have a great day and see you soon!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)